- Home

- Kristine Barnett

The Spark Page 2

The Spark Read online

Page 2

Confused by this unexpected visitor, I looked to my sister for an explanation. She pulled me aside to confide in a hushed whisper things that made no sense at all. She said that she’d invited this boy over so that we’d be forced to meet. She’d even called my boyfriend with an excuse to cancel our date that evening.

At first I was too dumbstruck to react. As it slowly dawned on me that Stephanie was trying to play Cupid, I truly thought she’d lost her mind. Who fixes up someone who’s hoping her boyfriend is about to propose?

I was furious. She and I hadn’t been raised to play the field. In fact, I hadn’t gone on my first date until I was in college. We certainly hadn’t been taught to be dishonest or disloyal either. What could she have been thinking? But as much as I felt like screaming at her—or storming out of the apartment altogether—we’d been raised with good manners, and Stephanie was counting on that.

I extended my hand to the boy, who was as much a pawn in Stephanie’s charade as I, and took a seat with him and my sister in the living room. Stilted chatter ensued, although I wasn’t really paying attention. When I finally looked at the boy, really registering him for the first time, I noticed his backward baseball cap, his bright eyes, and his ridiculous goatee. With his laid-back, scruffy appearance, I assumed that he lacked substance. The contrast with my crisply formal, preppy boyfriend could not have been more pronounced.

Why had Stephanie wanted us to meet? I was a country girl, from a family that for generations had lived a modest, simple life. Rick had shown me a very different world—one that included penthouses, car services, ski vacations, nice restaurants, and art gallery openings. Not that any of that mattered. Stephanie could have brought Brad Pitt into the living room, and I still would have been angry at her for disrespecting my relationship. But the contrast between this disheveled college student and the shiny penny I was seeing made me wonder all the more what my sister had been thinking.

Before long, Stephanie yanked me from my silent perch and, trying to find a bit of privacy within her tiny studio apartment, chided me sternly. “Where are your manners?” she demanded. “Yell at me later if you like, but give this boy the courtesy of a proper conversation.” She was, I saw immediately and with embarrassment, right. Being rude to a stranger—a guest!—was unacceptable. Courtesy and graciousness were qualities that had been instilled in us since birth by our parents, our grandparents, and the tight-knit community in which we’d been raised, and so far I had been as cold as ice.

Shamefaced, I went back to sit down and made my apologies to Michael. I told him that I was in a relationship and didn’t know what Stephanie could possibly have been thinking when she’d arranged this meeting. Of course, I explained, I wasn’t angry with him—only at my sister for putting the two of us in this ridiculous situation. With that out in the open, we laughed at the utter preposterousness of it and marveled at Stephanie’s audacity. The tension in the room eased considerably, and the three of us fell into easy conversation. Michael told me about his classes and about an idea he had for a screenplay.

That’s when I saw what Stephanie wanted me to see. The passion and drive that animated Michael when he spoke about his screenplay were unlike anything I’d seen in anyone I’d ever met. He sounded like me! I felt my stomach lurch and experienced a kind of vertigo. Instantly, I knew that my future, so certain only moments before, would not go according to plan. I would not be marrying my boyfriend. Although he was a wonderful man, that relationship was over. I had no choice in the matter. I’d known Michael Barnett for less than an hour, and yet with a certainty impossible to explain or defend, I already knew that I would be spending the rest of my life with him.

Michael and I drove to a coffee shop and talked the whole night through. As corny as it sounds, each of us felt as though we were reconnecting with someone we’d lost. Being with Michael felt like coming home. We were engaged three weeks later and married three months after that. And still, after sixteen years of marriage, it feels as necessary and right for me to be with Michael as it did on that first improbable night when we met.

The rest of my family did not embrace Michael immediately—or our whirlwind courtship and sudden engagement. What on earth had gotten into their sensible daughter? Even Stephanie, responsible for our meeting, was now as worried and confused as the others. True, she’d felt compelled to introduce us, but she didn’t understand how we could be so sure about a lifelong commitment in such a short time. Our differences were obvious to everyone, including the two of us: I was a sheltered country girl with deep spiritual roots, raised with the constancy of a loving family, while Michael was a city boy, raised on the wrong side of Chicago, with a tough family life.

Whereas I wouldn’t leave the house, even for a quick trip to the grocery store, without making sure every hair was in place, Michael, a leather-jacketed nonconformist, was unconcerned with outward trappings. Pride of home also was important to me. When I was growing up, you would have been more likely to come across a live chicken in our kitchen than to find a roll of paper towels or a stack of paper napkins—only slightly less true in my own home today. My world seemed utterly alien to Mike, who had grown up eating meals that were mostly catch-as-catch-can and seldom served at a table, and it provided endless fodder for his jokes.

Michael’s sharp wit and keen, satiric humor surely served to compound my family’s discomfort. Yet his ability to make me laugh—especially when things got tough (or when we began taking ourselves a little too seriously)—was one of the things that made me fall instantly in love with him.

My family’s deep and vocal concern was unanimous, with one exception. Grandpa John Henry saw something in Michael and took an instant shine to him. It was his opinion that carried the most weight with me, and so it meant the world to me when he said that he trusted my inner compass and that I should, too.

Life with Michael was my destiny and a certainty I didn’t question, but there was a wrenching consequence to our love: breaking with the church in which I had been raised—the church of my parents, and their parents, and many generations of my family before them.

I was raised Amish—not horse-and-buggy Amish, but city Amish. Like many Amish of their time, my grandparents wanted to embrace the modern world while still holding fast to their old-world traditions and beliefs. So they became part of a new order of Amish—sometimes referred to as the New Amish—who maintained their faith and community while making some concessions to modern life. We wore regular clothes, enjoyed modern conveniences, and went to public school. Even so, church for us was not just a Sunday event. It was the very fiber of our everyday lives.

In the Amish faith, if you don’t marry someone from the church to which you belong, you cannot remain a member of that church. My beloved grandpa John had himself been cast out of his when he’d wed for love. (Although my grandmother was Amish, she was not from the same community.) My father was not Amish, but when he proposed to my mother, he joined her church, allowing her to remain in the fold.

As difficult as it was to imagine breaking with a tradition so important to me, I had always known that the Amish custom of arranged marriages was simply not for me. Although there had been many offers for my hand, my dad (to my mother’s chagrin) had turned them all down. He also didn’t believe in arranged marriages, and certainly not for his own girls. As much as I loved my church and our way of life, if I couldn’t marry Michael and stay in the church, I really had no choice but to leave.

A Baby Boy

From day one, Jake was as affectionate and curious as a baby can be. He talked early and quickly learned the power of “Hi!” My sister, Stephanie, used to laugh at the way he could charm an entire restaurant by greeting everyone who passed by with a sunny wave. He loved stuffed animals and would hide himself in a heap of them, squealing with delight every time he was discovered.

I had, of course, already seen the softer side of Michael, but even I was tickled by the way he threw himself into the role of devoted dad. He was work

ing long hours at Target in those days, but even if he’d worked a double or an overnight shift, he would always find the energy to wrestle with Jake, WWF-style, on a big pile of couch cushions on the living room floor. One of baby Jake’s favorite games with Michael was to “share” a piece of cake—which mostly meant smearing frosting all over Michael’s face and laughing hysterically while his dad pretended to gobble up his hands.

I went back to work at my daycare less than a week after Jake was born. I was eager to return to work because I loved it, and having been on bed rest for so long, I was concerned about taking even more time off. I didn’t want to lose the trust of the families who had given me their children to take care of. Some days, I was in the daycare from six in the morning until seven at night, and Jake was right there with me. The kids treated him like a life-sized Cabbage Patch Kid. They dressed him up and sang songs to him and taught him to play patty-cake. I laughed to see how territorial some of the little girls in particular could be. “I should put her on the payroll,” I told one mom one evening when her daughter was finding it difficult to leave “her” baby, Jake, with me.

There were some early signs that Jake was quite clever. He learned the alphabet before he could walk, and he liked to recite it backward and forward. By the time he was one, he was sounding out short words such as “cat” and “dog” by himself. At ten months, he’d pull himself up using the arm of the couch so that he could insert his favorite CD-ROM into the computer. It contained a program that “read” Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat—and it sure looked to us as though he was following the little yellow ball bouncing on top of the words and reading along with it.

One night I found Michael standing outside Jake’s room after he’d put him down for the night. He put his finger over his lips and motioned for me to join him. I snuck up next to him to listen to our son, who was lying in his crib, sleepily babbling to himself—in what sounded like Japanese. We knew that he knew all of his DVDs by heart, and we’d seen him switch the language selection on the remote, but it came as a real shock to realize that he’d memorized not only the English versions but apparently much of the Spanish and Japanese versions, too.

We were also struck by Jake’s precision and dexterity, especially at an age when most boys are barreling their way through the world like miniature Godzillas. Not Jake, who would often sit quietly, meticulously lining up his Matchbox cars in a perfectly straight line all along the coffee table, using his finger to make sure the spacing between them was even as well. He would arrange thousands of Q-tips end to end on the carpet, creating elaborate, mazelike designs that covered the entire floor of a room. But if we felt the occasional swell of pride when it seemed as if Jake might be a little advanced compared to his peers, we were also aware that all new parents think that they have the most remarkable child on earth.

When Jake was about fourteen months old, however, we started to notice little changes in him. At first they were all minor enough that we could easily explain them away. He didn’t seem to be talking or smiling as much, but maybe he was cranky, or tired, or teething. He was prone that year to terrible and painful ear infections, one after another, which helped explain why he didn’t seem to laugh as hard when I tickled him, or why he would sometimes wander away when I covered my eyes to play peekaboo. He was no longer as eager to wrestle with his dad, a game he’d previously dropped anything to play, but maybe he just wasn’t in the mood. And yet, with each passing week, we noticed that he wasn’t as engaged, curious, or happy as he’d been. He no longer seemed like himself.

Jake seemed to be getting lost in some of his early interests. He had always been captivated by light and shadows and by geometric shapes. But now, his fascination with those things started to feel different to me.

We had discovered when he was very little, for instance, that he loved plaid. Our duvet cover at the time had a plaid pattern, and it was the only thing that would soothe him when his ears hurt. Just as other mothers won’t leave the house without a pacifier for their babies, I was never without a scrap of plaid material. But after that first year, he began to roll over onto his side and stare intently at the cover, his face just inches from the lines, and he’d stay there as long as we’d let him. Sometimes we’d find him fixated on a sunbeam on the wall, his body rigid with concentration, or lying on his back, moving his hand back and forth through the sunlight, just staring at the shadows he was making. I had been proud of and intrigued by the early signs of his independence, but these behaviors no longer felt like independence to me. They felt like he was being swallowed up by something I couldn’t see.

Jake had always been the coddled younger “sibling” in the daycare group, and he had loved every minute of it. He’d spent his whole first year finger-painting alongside the daycare kids and bouncing right along with them when they did Freeze Dance. He took his nap when they took their naps, and he ate his snack when they ate theirs. But now I found that he’d rather look at shadows than crawl after his favorite kids, and their most outrageous bids for his attention often went ignored.

Michael was sure I was worrying unnecessarily, rightly pointing out that children go through phases. “He’s fine, Kris. Whatever it is, he’ll grow out of it,” he’d reassure me, snuggling us tightly into a family bear hug, and eliciting a squeal of delight by nuzzling Jake’s ticklish tummy.

In fact, my mother was the first person in the family to suspect that whatever Jake was going through wasn’t just some funny toddler phase. We didn’t know it yet, but our perfect world was already starting to fray around the edges.

Something’s Wrong

I grew up in central Indiana, close to farm country. We even had some farm animals of our own out back, usually a goat or a rooster. Every spring, my mother would borrow a brand-new baby bird from a farm for the day. It was a tradition I loved as a child, one I looked forward to every year, so of course I couldn’t wait to share it with Jake.

Jake’s second spring, the adorable baby was a duckling. Fourteen-month-old Jake was sitting at the kitchen table in my grandmother’s house, filling page after construction paper page with hundreds of hand-drawn circles. They were strangely beautiful, but they were odd, too, more like the type of doodle you’d expect to find in the margins of an architect’s notepad than in the drawings of a child not yet two.

As my mother tenderly cupped the duckling to scoop it out of its wicker basket, I could barely keep the lid on my own giddy anticipation. Laughing at me, she put her finger to her lips as she snuck up behind Jake, placing the adorable little fuzz ball right on top of the paper where he was drawing.

But the reaction we expected never came. Jake didn’t light up with delight at the fluffy baby duck waddling inches in front of his nose. Instead, my son reached out one finger and gently pushed the duckling off his paper. He never stopped drawing his circles.

My mom’s eyes met mine again, and this time they registered fear. “I think you’ve got to get him checked out, Kris,” she said.

Our pediatrician immediately arranged for a hearing test, but there was nothing wrong with Jake’s hearing, even though by that time he was no longer reliably responding to his name when we called him. We all agreed it was time to have Jake evaluated by a developmental specialist. The doctor suggested that we contact First Steps, a state-funded early intervention program that provides assessments and therapy for children under the age of three who appear to have developmental delays.

After an initial assessment showed significant delays, First Steps sent a speech therapist to our house each week to do therapy with Jake. Despite these sessions, he spoke less and less as the weeks passed, retreating further and further into a private, silent world. His speech therapist ramped up the number of sessions to three a week, the maximum allowed by First Steps, and before long a developmental therapist was added to the team. We set up a therapy area in our kitchen, and I bought a big wall calendar to keep track of all the appointments. By this point, Jake was barely talking.

; Michael didn’t mind the stream of specialists coming in and out of our home every day, but privately he admitted that he thought it was overkill—a sign of the times, an overreaction. “Kids develop at their own rate, Kris. You’ve said so yourself. Not long ago, nobody would have been making such a fuss about this. Whatever he’s going through, he’ll grow out of it.” Still, if the state was willing to provide all these services to speed the process, that was okay, too. Michael was confident that Jake would be fine either way.

I was also feeling more optimistic, encouraged by the fact that we had our very own personal brigade of therapists. One of the children I’d taken care of when I was a live-in nanny had experienced some early speech problems, and I’d seen his speech therapist work wonders in an extremely short time. Surely, with all these experts helping us and a little elbow grease and patience, we’d get our boy back.

There were other reasons to rejoice as well. My daycare, Acorn Hill Academy, was thriving. Acorn Hill didn’t look like a typical daycare; it looked more like the backstage at a theater preparing for a production. Money was always far too tight for me to purchase the supplies I needed to fuel the children’s creative impulses from a proper crafts store, so I was constantly on the lookout for resourceful ways to get these materials. The number of possibilities that might spring from, say, a refrigerator box is staggering, and I discovered that as long as I was willing to haul such things away, people were happy to let me have them.

Before long, several stores in the neighborhood began saving boxes of throwaway items for me—boxes filled with treasures. One carpet store kept us well stocked with sample squares, and a paint store gave us old wallpaper books, along with specially mixed paint that people had ordered but not picked up, and damaged brushes. We always had one special project or adventure in the works: an enormous mural, for example, or a room-sized chess game (another donation!) with figures and pieces so large, the children had to form teams to move them.

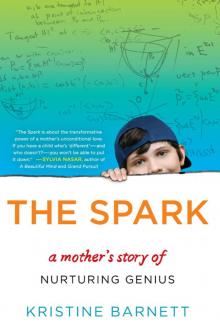

The Spark

The Spark